Right now, innovation around soils has momentum. Despite important gaps in scientific understanding, a combination of environmental concerns, farmers’ hunger for guidance and the impatience of entrepreneurial innovation means there’s no waiting for 100% certainty.

In this (lengthy!) post, the overdue Part 3 in Soil Series, I take a look at the innovation in this space and the commercial opportunities emerging. Agricultural practice – and capital – is moving at an exciting pace, and the next 10 years will be an important time for soils, the farming community and the environment.

It’s complex

In all things soil related, one size does not fit all. UK researcher Elizabeth Stockdale uses a analogy which is helpful here. She points out, we know 5 or 6 broad things important for human health (eg exercise regularly, eat fruit and veg). This does not mean we must all run marathons and eat kale. The specifics to satisfy these criteria can be different for different people.

Similarly, she points out, we broadly know 5-6 things that will improve soil (maintain cover, reduce tillage etc), but the specific actions need to flex according to a farm’s business model, soil type and so forth.

The analogy to the world of managing human health is also useful for thinking about the entrepreneurial opportunities around soils. In the human wellbeing space there is a vibrant market for health assessment hardware and software (from blood pressure monitors to fitbits), expertise and guidance to improve health (think: personal trainers, dieticians), and supplements to support or improve human health (eg vitamin pills, probiotics). The same is true for soils … it’s just that the market is a lot less mature.

After starting Part 1 with a primer on why soils matter, then discussing the barriers to taking action in Part 2, Part 3 focuses on the entrepreneurial opportunities, considered in the context of these four questions

- How do we measure soil health, or improvements in soil health?

- How can farmers and growers get guidance on which good soil practices might work for them?

- What soil supplements are available?

- What economic and financial business models are emerging to support soil improvement

It is these four questions I’ll dig into in here.

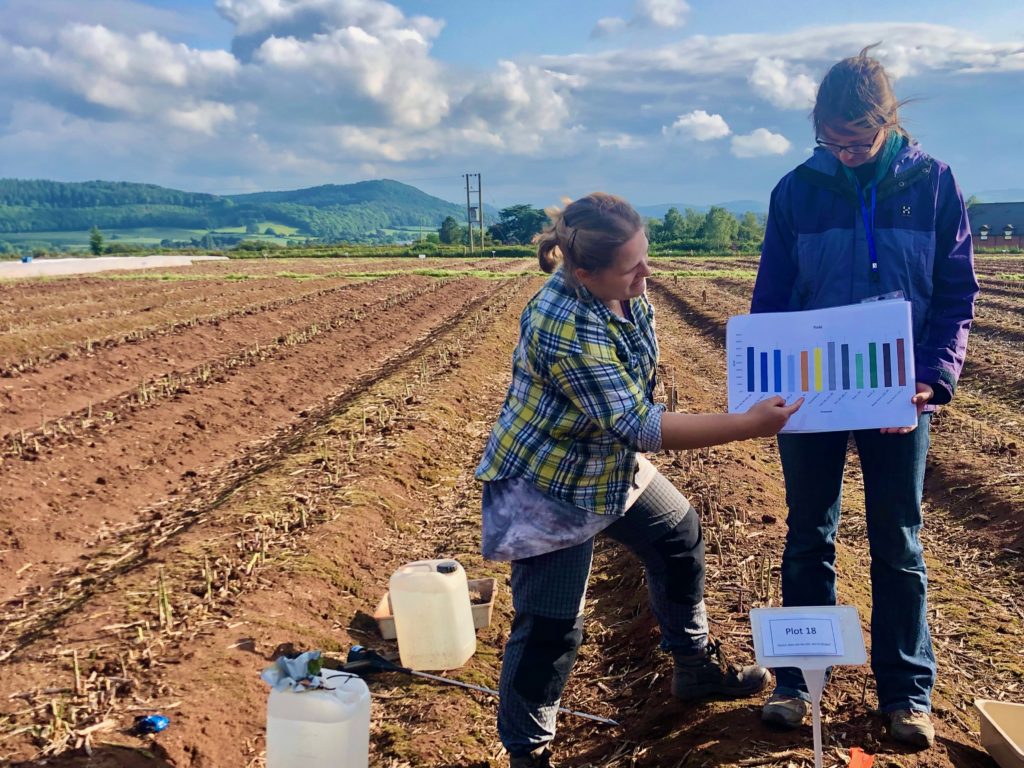

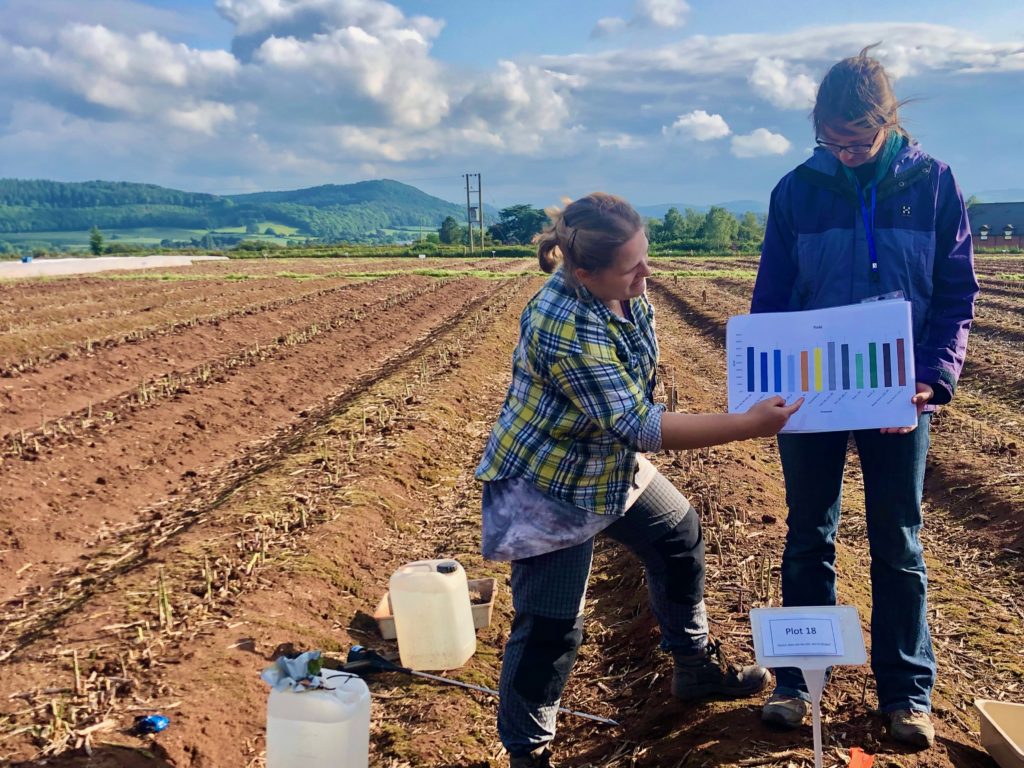

1. Measurement and Assessment

A cliché with more than a grain of truth is “what gets measured gets done”. When it comes to soil health, there is no single established method to measure your starting point, potential for improvement or progress towards that potential. Over and over the message is “it’s complex”.

Most agronomy companies offer a soil assessment service, involving on-site spade work plus samples sent to a lab for analysis. This is helpful, but poor temporal and spatial resolution are the Achilles heel of traditional soil assessment practices. Many farmers are now used to precision agriculture when it comes to above-ground characteristics, but this doesn’t transfer to under-ground characteristics. This matters, because the soils from this side of the field can be wildly different to the other side, let alone one field to the next, this side of the valley to that.

Rhiza approaches this challenge using satellite imagery to spot areas of a field which appear sub-optimal, for instance showing reduced chlorophyll intensity. The process then reverts to traditional spade work, but in a more targeted way focused on the affected areas, to investigate underlying reasons. Improvement measures can then to be integrated into location specific treatment using GPS agricultural targeting. For example one might chose to sub-soil just the area with the compaction.

However, Rhiza’s approach doesn’t deal with a second drawback of the “typical” agronomists soil assessment, namely limited insight into the soil’s biological health. Biological health is traditionally inferred from indicators such as lab-assessed soil organic matter evaluation or earthworm count. Yet soil biology is tremendously complex and these methods miss a great deal. Even tiny soil samples contain thousands of microorganism species and associated food webs. Prevalence of, and interactions between, these species varying by crop, geography, climate and more.

Despite science not having a full picture of what’s going on in our soils several companies accept and work with the “black box” limitations. We may not know all the elements of functioning, but if we can tell good from bad, problem X from problem Y, that’s a start.

For example, Trace Genomics. They provide insight into soil biology using metagenomic assessment of soil samples – evaluation of all the genetic material from all species in the sample, be they fungi, nematodes, algae or anything else. From this they suggest improvement steps that might be needed. Metagenomics is complex work involving intense computing power and extensive capital investment (Trace raised $13m Series A funding last year). So one of the ways they got traction by initially focusing on high value horticultural crops such as strawberries, thereby justifying the grower’s investment and limiting the diversity under investigation.

Several companies accept and work with the “black box” limitations.

Although the advent of robust biological assessment is a break through which clearly adds value, the lab-based assessment of this type suffers drawbacks. It takes time to get results, and there is limited scope for evaluation in high spatial resolution.

Another new company – PES Technologies – takes a different approach which, if successful, has the potential to overcome both of these challenges. They plan to use electronic nose technology, developing organic semiconductors to sense volatile chemical emissions from the soil. These signatures will then be used to train machine learning algorithms to distinguish healthy soils from less healthy.

The underlying assumption is that problem X – lets say compaction – affects the gaseous fingerprint of the soil ecosystem in a different way from problem Y – eg presence of a pathogen. They by training algorithms on the volatile organic chemicals emitted by small samples of soil with known properties, it is hoped those characteristics can be distinguished and improvement programmes developed. If this is proven (and with a proof of concept under their belt, it seems that the idea has mileage) the approach has the potential to have a very low cost per sample, and could perhaps be integrated with farm robotics to allow greater spatial resolution and reduce manual intervention.

2. Management Practices, Regenerative Agriculture

Many organisations give advice and support to soil-conscious growers. Agronomy companies are perhaps the natural first port of call for many farmers, acting in the role of consultant for all manner of agricultural questions.

Nonetheless, many of the most compelling visions and dramatic results in soil improvement come from the “Regenerative Agriculture” movement. The term Regenerative Agriculture is open to many interpretations, so here I”m using the Croatan Institute definition: “holistic approaches to agricultural systems that work with natural systems to restore, improve, and enhance the biological vitality, carrying capacity, and “ecosystem services” of farming landscapes. Regenerative farming operations also aim to support the resilience of the rural communities and broader value chains in which they are situated.”

“This can set soil improvement advice antagonistically at odds with “conventional agriculture” and often with traditional agronomy.”

As this quote makes clear, the practices associated with soil and ecosystem regeneration are often tied up with other world-view perspectives associated with smaller scale and localised production. This can set soil improvement advice antagonistically at odds with “conventional agriculture” and often with traditional agronomy. Similarly much of the knowledge about how to integrate regenerative practices has historically been share in an analogue way, and is subject to much trial and error. All of these factors means adoption of soil friendly practices has largely been disconnected from digital farm management platforms that many “main stream” farmers use (eg Bayer’s Fieldview).

There exists, therefore, an opportunity to take the expertise around of soil management best practice as demonstrated in the regenerative agriculture movement, and integrate it with the digital and precision agriculture ways of working.

EFC Systems’s AgSolver platform integrates precision machine data with GPS data sources to allow US based row-crop farmers to manage their farm for profitability. EFC Systems is not borne of a sustainability or regenerative agenda, but they do offer an environmental analysis framework to evaluate soil erosion, nitrate leaching etc alongside their core business management insights. In addition, environmental benefit can come from a focus on profitability over yield, because the financial impact of practices such as cover crop use and reduced tillage can mean savings on input costs (eg less fuel and labour used to plough, less fertiliser required) which compensates for any yield reduction. The USDA’s carbon and greenhouse gas accounting system COMET-Farm is an example of similar public sector intervention in this space.

In contrast, and coming from an explicitly Regenerative Agriculture background, seed-stage start-up RegenFARM is more explicitly aimed at assisting in the transition to regenerative practices. Their plan is to integrate multiple data sets to enable farmers to simulate the costs and benefits of soil and environment friendly practices, thereby building confidence in the costs, risks and benefits associated with taking regenerative steps and encouraging step-wise migration to alternative practices.

3. Soil Improvement, Remediation Additives

Are there additives that can be used to accelerate or assist the soil improvement process? The short answer is Yes. Will they work in a given setting? Unclear.

A burgeoning sector in soil additives and treatments is emerging, often aiming to create a more benign environment for a healthy soil ecosystem to develop, or to adjust an unhealthy ecosystem by addition of beneficial microbes. (For brevity, my focus here is on treatments to influence soil in general, not just the rhizosphere, the thin region of soil around the roots).

Biochar is one type of soil improvement product, a catch-all term for organic matter which has been carbonised by pyrolysis leaving a blackened, solid residue which persists in the soil. It is thought to assist with structure, water and nutrient retention capability, and increases the surface area for the soil’s microbiome to flourish and, despite the high temperatures required to make biochar, it is also believed to be a highly effective carbon sequestration mechanism because it doesn’t really degrade in the soil.

Coolplanet is possibly one of the highest profile proponents of biochar, earning a recent listing in this year’s Thrive’s Top 50 Agtech Landscape listing. A similar start-up in the same space is Carbogenics, whose USP is the using a mountain of disposable (but rarely recycled) coffee cups as feedstock, thereby addressing another 21stcentury challenge

Emergent companies need to spend significant sums to demonstrate where, when and how their products benefit crop production and soil health.

Coolplanet could almost be called ag-tech veterans, benefiting as they do 10 years of research and data. That wealth of evidence matters in the world of soil additives especially because, given the complexity of soil biology, the science behind the marketing claims for soil additives is often hotly contested. “Snake oil” is a common allegation to overcome! Emergent companies need to spend significant sums to demonstrate where, when and how their products benefit crop production and soil health.

This is especially true for companies that focus on supplementing the soil microbiome – think prebiotics and probiotics for the soil. Examples here include Canadian company AgSol and Australian Nutri-Tech Solutions both market products specifically designed to add beneficial microbes to the soil (eg Azoterbacter, arbuscular mychorrizal fungi) which they report yields a range of benefits such as improved nutrient drought tolerance and nutrient uptake.

Start-up company Microgen Biotech focuses in particular on using microbiology to remediate contaminated soils. Their flagship process identifies and deploys microbes to degrade or immobilise soil contaminants, a process relevant to extraction industries in general (oil, coal, gas etc) and to specific geographies (eg China) where enormous quantities of agricultural land are contaminated by industrial pollutants.

“there are significant tools in the soil improvement arsenal from novel cover crops”

Lastly – while not a soil additive – there are significant tools in the soil improvement arsenal, from novel cover crops developed not only to slot into the annual growth cycle during periods when fields would typically be left bare (eg over winter), but also to generate additional farm income. The farmer benefits from an extra cash crop in the year, the soil benefits from greater year-round cover.

Covercress has developed a fast-growing and high-yielding version of a native US weed pennycress (see this post about Gene Editing) while Agrisoma market a variety of Ethiopian Mustard sold as Carinata to fill the bare soils between soy and corn rotations. In both cases the resulting crop produces oil (last year the first commercial transatlantic and transpacific flights fuelled by 30% Carinata were conducted) and a high protein meal for livestock.

4. Investment and Financial Incentives

A final category of opportunity – not really Agtech, but hugely relevant to this topic – the might hand of finance. The investment community has woken up to the idea that there is money to be made by focusing on soil health, and not only is this financially rewarding, it makes an attractive carbon-sequestering addition to the portfolio at a time when a lot of money managers are keen to enhance their sustainability profile.

The Croatan Institute produced a report specifically about investing in “soil wealth” (“the constellation of benefits associated with building soil health and community wealth through regenerative agriculture”). They report, in the US alone, $47.5bn of assets under management focused specifically on sustainable and regenerative agriculture.

One form this takes is investing in the carbon sequestration possibilities of soil. State-level carbon trading schemes (eg California, European Union) have typically steered clear of soil related sequestration opportunities, often because of the challenges of measuring practices undertaken and results generated mentioned above. Whereas historically benefits primarily accused to farmers improving already degraded soils or poor environmental practices (see this Modern Farmer article) this is steadily changing.

Indigo Ag has also been active in this space, setting up a carbon trading platform to supplement their microbial biostimulant activities and digital grain trading marketplace. While $15/ton Co2 sequestered offered by Indigo won’t transform the economics of arable farming, it certainly won’t hurt either.

“A farmer wanting to invest in restoring her soils is analogous to a dilapidated hotel manager wanting to invest in refurbishment.”

Traditionally farming businesses are valued on real estate value and expectations around commodity prices. Nicolas Choksi, a Scmitt McArthur Fellow, points out that soil should more properly be considered an agricultural asset which practices may deplete and therefore need ongoing maintenance. He suggests that a farmer wanting to invest in restoring her soils is analogous to a dilapidated hotel manager wanting to invest in refurbishment. A capital injection and reduced cash flow short term is required to see longer term growth in the profitability and stability of the business.

There is a small but notable business model in providing loans through the private debt market to companies with a regenerative or sustainable orientation addressing an access to capital gap for farmers (especially small and mid-sized farmers) wanting to finance investment in soil health even if this means a short term impact on cash flow or profitability. The Maine Farm Business Loan is an example of this, and, characteristic of many in this market, it explicitly focused on local markets. Others may prioritise pursuit of their charitable mission over generating market rate returns.

Financial innovation also exists around direct investment in farms engaging in soil improvement then increasing the value of that land using regenerative agriculture practices to boost soil health; the agricultural equivalent of property redevelopment. Sometimes this process is coupled with financing inter-generational transfer of farms and ranches, sometimes the land may managed productively before realising capital appreciation during re-sale of the land. Examples of innovators in this investment-in-regeneration space include

- Beartooth Capital, who focus on restoring environmentally distressed ranch land in the Western USA;

- Dirt Capital, who partner with farmers in the North East USA who want to invest in or expand their farms using a conservation or organic approach.

- SLM Partners a similar investment company, but more international in orientation focused in the UK, Ireland, Australia and North America.

So what have we learnt from all this?

Good soil management undoubtedly has benefits. The benefits extend beyond public goods of flood reduction, carbon sequestration and ecological diversity, to financial benefits for growers, landowners, innovators and investors.

After years of stasis, innovation in soil management, measurement, investment and intervention is booming, and these different aspects have potential to intersect and synergise.

“It will be exciting to see what the building confluence of capital, innovation and knowledge will achieve.”

There is still masses of room for more innovation. To name just one opportunity, scaling financial investment in soil regeneration depends on holding recipients of finance to account by tracking soil health improvements in a robust, rapid and reliable way. The soil health entrepreneurial ecosystem has work to do! And while much of the fundamental science that still remains to be discovered, when it is it will surely open further opportunities for innovation.

Farmers who invest in soil see long term benefits in ability to cope with biotic and abiotic challenges to their production cycles. Entrepreneurs who provide tools, seeds and services that facilitate soil stewardship are standing on the edge of tremendous market potential as soil health moves from being a niche preoccupation to a mainstream concern.

It will be exciting to see what the building confluence of capital, innovation and knowledge will achieve. Soils are fascinating – and will continue to be so for a long time to come.